One

of my brother's friends and co-writers kept bugging him to “write

what you know about.” This dictum supposedly allows one to truly

put down on paper the depths of your heart and soul.

“Ken,

write about your disease!” He was advised.

My

brother suffered from an Edwardian etiquette that would force him to

put his troubles aside for others, including terminal illness.

Bothering others with your own problems was NOT allowed. If you

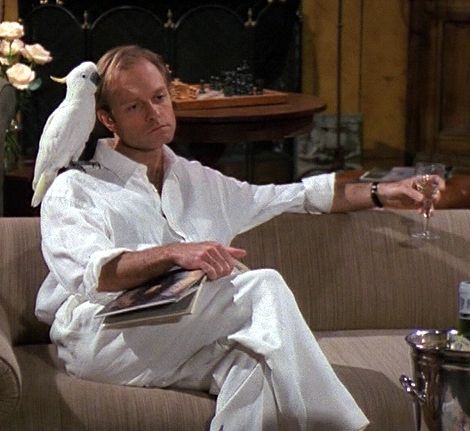

want to get a bird's eye view on his personality, think of Niles

Crane from the show Fraiser. That was my brother in spades (minus the cockatoo).

The

following was his final piece before he died and satisfied his friend

about “writing what you know about.”

I

warn you now. What comes gets disgusting, at times sad, bleak and

extremely personal. I read his story at the publishers before it

went to print. I did not know the real depth he

managed to hide the trials he undergone. I knew what crap he had to

deal with but he managed to keep the worst within himself so well.

*****

From

the East Side Monthly/Providence Monthly, December 2003.

Withering Heights

A

kind, gentle creative Spirit Succumbs to Disease.

Ken

Mahan was a talented musician and writer who worked for the past

eight years as a member of the United Way marketing team here on the

East Side, as well as a columnist for this paper but regularly for

our sister publication Providence Monthly. Just this month, Ken lost

his twenty year battle with the debilitating disease known as cystic

fibrosis. What follows is a journal Ken kept to document his final

thoughts, frustrations and hopes during the last few months. Perhaps

one of the kindest and most sensitive individuals many of us have

ever met, Ken's insights and humor remained intact to the end and

despite this harrowing ordeal.

PLEASE

STOP ME FROM DISAPPEARING IN MY OWN CLOTHES!

“Not

again” I whisper in exhaustion, watching gobs of phlegm streaked

heavy with blood sliding around then disappearing down the drain in

the bathroom sink. I had coughed deeply, sending needles of pain

through my inflamed lungs . The blood means my lungs are infected

again. It is a cold morning and I am trying to get myself ready for

work.

I

feel sick, but usually I drag myself through work and other

activities. Sometimes, as a way to keep moving forward, I am

needlessly harsh with myself. I will tell myself that life is about

suffering anyway, and if I feel sick, unhappy and unfulfilled, then

the least I can do is to keep my mouth shut and not burden others

with it. I generally try to avoid the subject of my illness

altogether, unless I am cornered into talking about it. I am often

fearful that over time I would just sound like someone who complains

too much.

Alone

in the kitchen, with the sunlight glaring at me through the window, I

feel like crying as I open the prescription bottles of antibiotics.

I am so tired of taking them repeatedly for weeks on end. The Cipro

and Dicloxacilin eventually control the infection, but in the

meantime, they give me fatigue, diarrhea and nausea. I can sense the

antibiotics while they are in my system. I feel like I've been

lowered into a vat and immersed in some kind of nagging chemicals

that put my in a wearing state of suspense, making me tired but not

letting me sleep peacefully.

I

am thin. A side effect of the antibiotics is that sometimes food

seems unpalatable. A ham sandwich tastes like it has gone bad, while

a meatball sub has a very strong taste of iron. I feel less inclined

to eat, and I lose weight. On this particular day, I am five foot

ten and 117 pounds. In a mirror, my arms are slender and, I have to

admit, more feminine looking than masculine. My stomach is flat and

the outline of my ribcage is easily visible. I feel ashamed.

There

are enzyme pills I take to help my body absorb nutrients. Each day, I

am supposed to take 30 of them with each meal or snack. As I walk

toward the bathroom, I am seized by a coughing fit and I have to stop

until it passes. Staircases and hills make me huff and puff from

shortness of breath.

I

fear my physical life is becoming increasingly restricted. Several of

my neighbors are elderly people; they walk slowly, their movements

are gentle, and their presence suggests a kind fragility. Although I

am just 44, I feel at times that I am prematurely turning into one of

them.

At

times, the stress of chronic sickness seems to reduce me to a small

boy who understandably wants to be comforted, and who cannot fathom

why he is continually being punished. Illness can make you earnestly

hope that there indeed is a merciful God who hears you and might

deliver you from suffering. A protracted illness also tends to put

pressure on whatever your particular neurosis might be, in my case,

tendencies toward unfair self criticism and depression. It often

takes a concerted effort to keep those destructive urges at bay.

On

some very trying days, however, when the illness has been wearing on

me, I sometimes slide into tormenting myself with thoughts of

shameful inadequacy. An unassuming, mild-mannered man, I worry that

I am merely timid, weak, fearful, and have accomplished little in

life. Looking back, I tend to dismiss the good things I have done as

inconsequential, and instead I see many instances of procrastination,

negative thinking, getting discouraged, and not doing enough to fight

back against my fears.

Friends

meanwhile seem to lead more full, healthier lives, they ask for what

they want, they work through their fears, they achieve goals, and

they find a reasonable degree of happiness. When illness has

exhausted me physically and depression has gotten the better of me

for a time, I want to lay my head on someone's shoulder and say,

“Please, I don't want to be sick anymore. If I did anything wrong

or I'm just a failure, I'm so sorry. I didn't mean to be. I never

wanted to hurt anybody, or bother anyone. I am so sorry for being

what I am, but please let me not be sick anymore. Please let me stop

coughing. Please let me stop gasping for air. Please make my chest

stop hurting. Please stop me from disappearing in my own clothes.”

I

breathe in and out quickly, trying to get enough air. My chest rises

and falls. I sit on the bed and try to calm myself. I see the red

digits on the clock. In a few minutes, I will have to drive to work.

When

I arrive at the workplace, I park my car. Taking small steps as I

cross the parking lot, I hope that none of my co-workers will appear

and want to chat with me as we walk inside, because I can barely

talk. Once inside, I lean on a railing for a few minutes. I get to

my desk finally and I collapse into my chair. I am momentarily

relieved, but I did not know that things were about to take a turn

for the worse.

SERVING

TIME IN SOLITARY

We

all expect some suffering in life, whether it is a physical ailment

like a sprained ankle or external difficulty like a broken window.

There is pain or hardship, some application or remedy, and then

relief and a reassuring sense of having some control over one's

destiny. Chronic illness, however, does not relent, and can begin to

feel like a life sentence imposed for some terrible personal flaw or

wrongdoing. Not being able to get enough air is a panicky,

frightening feeling, and it is particularly so when you are isolated,

far from friends and familiar things. In that hierarchy of human

needs, being deprived of air trumps any other concern. Air must be

restored.

One

afternoon while walking along Hope Street in Providence, for no

apparent reason, I could not seem to inhale. I felt that the hand of

God had reached down from the sky to block my windpipe. In the

midst of that calm, pleasant, languid summer day, people meandered on

Hope, drove their cars, and went about their proverbial business

unaware that the slender middle-aged man with the dark blond hair

and the blue eyes was strangling to death in the middle of the

sidewalk.

After

some coughing, I got some air finally. With some other interruptions

of shortness of breath, it took me an hour to take a 30 minute walk.

I thought about calling someone to give me a ride, but felt too

ridiculous. “Listen, if you're not too busy, could you give me a

ride for about three blocks? Otherwise it's going to take me the rest

of my life to get to Rochambeau Ave.”

Another

day at home, some phlegm is stuck in my chest and I try to cough it

out, but it seems intractable. As I continue to cough, my chest

begins to feel inflamed; each additional cough feels like quick slash

of a razor. Suddenly my face is terribly warm, I seem to be just

barely getting enough air, and I am very scared. I wonder if I

should call 911. In a way, what scares me the most is that I am

alone, with no soothing voice near or hand gently clasping mine. I

would never want to die like this, by myself in an empty house. I

wonder if I should call a friend, if just the sound of a concerned,

familiar voice would calm me. I finally try a dose of Pulmozyme, a

mucus thinning aerosol that is used in a nebulizer, a small air

compressor that turns liquid drugs into a vapor I can use. At first,

I can barely inhale it. My heart is beating quickly.

It's

getting better now, it's getting better now. I gently repeat in my

mind, hoping to make it come true. Shortly, I manage to cough out

the phlegm. The coughing can be a terrible paradox. My body induces

spastic coughing fits because it is trying to expel the junk in my

lungs, but the coughing itself, which goes outward, makes it

difficult to inhale, and I frantically suck bits of air between

coughs. I involuntary jerk back and forth, as some demon takes

possession of my body.

A

MERE BAGEL

Lately,

I cannot seem to walk very far without pausing to rest and catch my

breath. I had often had trouble hauling myself up inclines and

hills, but this is happening now in my office or on a level sidewalk,

places where it should be fairly easy to walk.

The

Daily Bread Cafe is just over a block away from my workplace at

United Way, the corner of Wayland and Waterman. I cannot make the

distance anymore without stopping. I have certain strategic points I

use. On the corner of Medway street is a public trash can on which I

can lean on for a few minutes, odd as it may look to a passerby. A

funeral home has a nice low stone wall where I can sit. I suppose

from a certain point of view, there is something ironic about

frequenting the funeral home like it is some kind of idyllic park

bench on Blackstone Blvd.

One

cold, raw day, I made the trudge to Daily Bread with great

difficulty. The weather was foul, but I felt the need to escape, at

least temporarily the office's sterile cubicles, hallways, and

fluorescent lights. Thus I braved the raging elements in quest of a

bagel or muffin. My breathing was labored as I walked through the

cold little bullets of rain and endless wind. A mere bagel seems

hardly worth the stress of this simple outing is giving me, but for

years I have dragged myself forward, perhaps desperately than

doggedly, and I am afraid that if I relent I will somehow finally

lose control of my life.

When

I arrive at the cafe, I enter, relieved to be in it's warm, cozy

environs, but as I look at the staff behind the counter, I realize

that I am so out of breath that I cannot talk. For the moment, I sit

at a nearby table to collect myself. I am breathing heavily, my

jacket is slick and sagging with cold dampness. My eyes are

watering. On my table I have nothing, of course, because I haven't

ordered anything.

“Here,

take this,” says a man about 40 years old. He drops a dollar on

the table in front of me. “Get yourself a cup of coffee,” he

says helpfully.

Because

of my haggard appearance, he thinks I am a homeless man. After being

confused for a moment, I hand the dollar back to him. “No, no, I

have money,” I say. He believes me and accepts it.

I

live in a modest suburban home in Pawtucket. I am far from homeless,

but apparently I can look pale, gaunt and distraught enough to cause

someone to think that I am homeless. When I finally calm down, I

order my damned bagel.

THE

SMOKING GUN

I

was not diagnosed with cystic fibrosis until I was 25, which is

unusual in that most people are diagnosed as children. As a youth,

my symptoms were perhaps not as pronounced, or they were dismissed as

the usual cycle of colds and flu that children experience. I

forever, though, seemed to have colds.

Years

later, my mother told me that a pediatrician had suspected I had

respiratory problems and told her and my father to take me to a

specialist, presumably a pulmonary doctor. They chose not to do so,

and when I asked my mother why they made this decision. “I don't

know,” she said.

“You

don't know?” I asked incredulously. “What do you mean, you don't

know?”

“I

don't know” she responded.

I

was not angry or upset, but I was perplexed. Perhaps they feared a

specialist was too much money.

Whatever

concerns my parents may have had about respiratory problems, vanished

into the thin air, it seemed, as they proceeded to turn our house in

the 1960's into a veritable gas chamber with cigarette smoke.

Sitting at the kitchen table each night, my parents puffed on

Newports, their carcinogen delivery system of choice. They struck

matches from cardboard matchbooks with cheerful little advertisements

for the Old Stone Bank and the Checker Club restaurant. The matches

flared, then gave a hot, bright orange glow to the end of a fresh

cigarette. Stinking ashtrays were chock full of butts and dirty

ashes. I recall one ashtray that was sculpted in the likeness of a

lovely, yellow flower. It seemed strange to me to make something so

nice for the express purpose of defiling it with disgusting cigarette

butts, the filter ends damp with saliva.

As

the plumes of smoke rose and turned lazily, the kitchen ceiling

gradually took on a sick, brownish hue. In summer, some clean air

came through the screen door, but in the predominately cold New

England weather, our doors and windows were naturally closed most of

the time, trapping the smoke, and encouraging it to creep around the

walls and the ceilings like malevolent, wispy vipers.

This

was the air I breathed for years. Second hand smoke was my constant

companion. Once again, I am not so much angry now, but saddened that

everyone's health was compromised for the sake of sucking on several

thousand cigarettes over the course of however many years my parents

did so. To be fair, I am really not sure if the smoking had that

much effect on my lungs, but it certainly could not have helped

matters.

I

am sure of some other things, however. Every morning, my father

would awaken and launch into a hacking cough that you could hear up

and down the our street. This is no joke as my childhood friends tell

me they could hear it. He was an executive at a savings and loan,

and in his considered medical opinion, he did not have a problem with

smoking. He attributed his orgy of coughing to a dreaded condition

known as “post nasal drip,” i.e. mucous moving from the sinuses

the back of the throat. They only treatment for post nasal drip was

Dristan, an over the counter drug always at the ready in our medicine

cabinet. All the Dristan in the world, however, did not seem to stem

that morning ritual of labored, ragged and sharp coughing fits.

When

I worked briefly at the savings and loan as a teenager, I saw he had

a good sized mound of cigarette butts on his desk as well. It seemed

the only time he did not smoke was when he was asleep. Perhaps even

then he dreamed pleasantly about lighting a Newport and taking a

nice, long drag.

At

46, my father developed pneumonia, slumped then crashed onto our

kitchen table with the stained ceiling above him and died on a bleak

February day. As a teenager, I did not appreciate the thought that

46 is far too young to die like that.

At

65, my mother, though she had finally quit smoking a few years

earlier, developed emphysema, a painful constriction of the airways

that keeps you from exerting yourself for lack of air. It is a slow,

maddening disease. Watching someone die from emphysema is like

witnessing a crucifixion. The person is still alive, clinging to

live, but you know it is simply a matter of grueling time before the

inevitable occurs. She was bed ridden and had hospice care for about

a month, until she, too, died on a bleak day in February.

It

is not unusual to bury your parents, on the contrary, it would seem

the natural order of things, but there is something disturbing about

watching them die unnecessarily from a mundane vice. I am

fortunate, I do not smoke, not because I have some great moral

rectitude that forbids it, rather because I do not like it. Perhaps

I got enough of it as a child. Nowadays it does not seem exotic or

hip to me. I never preach at anyone, but when I see smokers, I feel

the urge to ask them if they ever imagined what it is like to be

gasping for air in a hospital bed. I meanwhile at 44 am wrestling

with what I have been told is end-stage cystic fibrosis. Perhaps it

is stubborn denial, but somehow I still think I will live for years,

in spit of what my doctor calls the “disease process,” i.e. the

gradual damage happening to my lungs as infections occur. It would

be nice to get past 46 and at least outlive my father, so to speak.

MUCOUS

WAS MY FRIEND

On

a practical level, cystic fibrosis is all about living with mucous

and lots of it. There is an ongoing need to expel it, a need that

becomes particularly crucial when an infection causes even more

mucous to accumulate, threatening to block your ability to inhale

air. As a youth, long before I knew I had cystic fibrosis, mucous

was my friend, one might say, a sort of amusing plaything.

During

a certain phase of their development, spitting is extremely important

to boys, either as an act of aggression, a way to mark territory or

some odd attempt to look cool. It is not uncommon for boys to have

spitting contests for distance, or to while away the hours spitting

at a wall. Because my mucous was unnaturally thick, it had more mass

and was easier to pitch forward with greater force for longer

distances. It is easier to throw a golf ball than a cotton ball

because the golf ball has greater mass. Due to this scientific

principle, I was able to distinguish myself by employing my mucous as

a weapon of sorts, inhaling deeply and blasting the gobs as far as

possible. There was also a small thrill when the gunk would land

with an actual audible slap against a wall or other surface, during

that blissful period in a boy's life when anything gross and

disgusting could not be more enjoyable. The other boy's mere saliva

was paltry in competition to my mucous. They spat a few feet while I

launched veritable intercontinental ballistic missiles that cruised

through the air for an appreciable time before it splattered with

great effect on the pavement.

According

to a sort of unwritten Geneva Convention, we did not spit on each

other generally, but wherever there are weapons, of course, things

can unexpectedly go awry. One afternoon at our neighborhood hangout

at a substation behind a shopping plaza, most of the gang were not

present. It was only myself and Ellen Harris. We were not

particularly found of one another, nor were we very mature about

dealing with the opposite sex. Ellen stood sullenly on one side of

the substation and I on the other, unable to see her. After a while,

out of sheer boredom, I decided to see how far I could spit straight

up into the air. With a hearty thrust, I blasted a glob of mucous

surprisingly high into the air. Rather than go straight up and down,

however, it rather described a parabolic arch, hurtling downward

toward the other side of the substation. A heart rending scream

rang out. Ellen had been hit. She might have cried “Medic!”

Instead asserted angrily, “I'm going to get my brother to kick your

ass!” For my own part, I was initially horrified, but then rapidly

the humor of the episode overtook everything and I laughed.

Fortunately, Ellen never made good on her threat, or perhaps her

brother did not think spitting on his sister was any great

infraction.

FOLLWING

DOCTORS ORDERS

The

staff at the cystic fibrosis clinic at Rhode Island Hospital are very

patient and helpful. Dr. Donat is very knowledgeable, thorough man

with a slightly whimsical bedside manner. Pam, a nurse, is very

efficient and kind-hearted. Stephanie is a nutritionist and has a

charming German accent. She quietly radiates iron will.

“You

will have peanut butter and crackers for a mid-afternoon snack, yes?”

Replying

anything other than “yes” to her seems unthinkable.

Their

initial assessment is that I need to gain weight and follow a regimen

of medications so as to make myself a good candidate for a lung

transplant. Cystic fibrosis is making my lungs deteriorate. I very

much hope to get a lung transplant. They give me loads of

milkshakes, vitamins and enzymes to get me stared.

I

did well at first, but there is a very old saying, “The spirit is

willing but Kenneth R. Mahan is weak” or something to that effect.

Partly out of sloth and partly depression, my compliance with the

regimen became inconsistent.

At

the same time, the pronounced fatigue that was making me cling to

trash cans on my way to the Daily Bread was getting worse. At my

desk at work, it was difficult to hold my head up. I would retreat

to a men's room that had a small couch and sit with my head in my

hands, wondering how I could be continually be so tired. Moving

around the office, I kept an eye out for empty chairs where I could

sit and collect myself before making that final 75 foot trek back to

my desk.

I

went to see my doctor, unsure if he could really do anything about

this problem. To my surprise, he quickly concluded that the time had

come to put me on oxygen 24 hours a day. I was perpetually tired

simply because my lungs, damaged by years of infections and

pneumonias, were no longer absorbing enough oxygen from the ordinary

air. For the foreseeable future, I would be unable to work.

I

look at the cool, grey sky, my lungs burning and I beg forgiveness,

for a chance to redeem myself and end the roiling pain in my chest.

Ken

died several days later, on December 18th, leaving behind

an army of friends and writing colleagues.

*****

The

last time I read this article was nine years ago. I found it the

other day while digging through a drawer fishing for some batteries. Once

again, perspective rears it's wise head. As I re-read this, I didn't

think of Ken, but of myself. Aren't I a selfish bastard? The person I was then, nine years ago,

is a bit different than the one today. It's been nine years, so this story of his reads different to me.

You get older, you learn about yourself more and more. There is a clarity that comes with age and it advances always. Though in my case, I tend to need certain mileposts to make me aware, like the re-read of the the story above.

You get older, you learn about yourself more and more. There is a clarity that comes with age and it advances always. Though in my case, I tend to need certain mileposts to make me aware, like the re-read of the the story above.

No comments:

Post a Comment